In the fall of 2014, I quit taking the SSRI I had been on for 13 years because it wasn’t “natural.” It was one of the biggest mistakes I ever made.

I was in my early 30s at the time, and very closely identified with the values of the wellness community. I loved green smoothies. I loved yoga. I loved the idea of only putting food into my body that was clean, organic, and pure. Goop, the natural lifestyle brand of Gwyneth Paltrow fame, had recently published an interview with a holistic psychiatrist about tapering off of antidepressants, which admittedly, was very responsibly written and by no means encouraged its readers to run out and stop taking their SSRIs. But it influenced me. An evening spent reading about the possibility of SSRIs being no more effective than a placebo and causing side effects such as decreased libido and emotional numbness were enough to make me drop those pills cold. I’m impulsive and prone to black-and-white thinking, and I stopped taking my antidepressants immediately.

Adaptogens have become very hip and trendy in recent years, and there is a polite but pervasive air of taint, corruption, and failure associated with pharmaceutical medication in the wellness community. Medication is synthetic. It’s chemical. Unclean. Impure. Full of toxic side effects. If you’re eating healthy, taking the right supplements, studying mindfulness, and practicing meditation, you should be able to cure yourself. And if you’re still struggling, you probably just need more maca, ashwagandha, and perhaps some extra spirulina to help rid your system of the heavy metal toxicity that is suppressing your neurotransmitter levels. A few pastel colored CBD bliss balls couldn’t hurt, either.

I do think wellness influencers have good intentions, antidepressants are overprescribed, and that adaptogens can be helpful for some people. But just because adaptogens are natural and “clean” doesn’t mean they are harmless. They are powerful medicines, just like conventional drugs. While this means they can do as much good as conventional drugs, it also means that they have just as much potential to do harm, especially to someone with delicate brain chemistry. The phenomenon of the influencer who partners with a brand, recommends an herb or supplement, and then tacks on a well-meaning but ultimately ass-covering disclaimer such as “always talk to your doctor before taking any new herb or supplement” is bullshit. My experience has been that most doctors of conventional medicine have no understanding of what these herbs and supplements do, how they interact with conventional medication, and are generally mute on the subject (I suspect for liability reasons). I know this because my post-Goop article brain was fried by a potent cocktail of herbal and pharmaceutical medicine all while being routinely monitored by a conventional MD, a psychotherapist, and a naturopath. The problem was we didn’t know I was bipolar.

Bipolar disorder is often misdiagnosed as depression. And undiagnosed bipolar people who are suffering from depression and seek help are generally prescribed antidepressants just like the next person. But most antidepressants make bipolar disorder worse. This includes “natural antidepressants” such as St. John’s wort and 5-HTP, among others. The antidepressant I dropped cold turkey was Lexapro, which some bipolar people tolerate, and in the months that followed my quitting, it became very clear that the Lexapro had indeed been doing something to help me, as I slowly fell into the most debilitating depression of my life. It was during this time that I truly came to understand the metaphor of The Bell Jar.

The Bell Jar tells the story of Esther Greenwood, a 1950s college student and aspiring poet who takes a summer internship at a womens’ magazine in New York City. But she doesn’t have a great time. She doesn’t connect with the content of the magazine or the women around her. She struggles with a sense of doom regarding her aspiration to become a poet, and anxiety in relation to how she will earn a living and survive as an adult in a society without smothering her artistic dreams. Upon returning home, she learns she was rejected from a prestigious writing course she applied to, falls into a severe depression, and is shuffled among doctors who attempt to treat her but seem to have no idea what they’re doing. The novel is a semi-autobiographical account of Sylvia Plath’s own experience.

I first read The Bell Jar when I was 15 in my high school English class. I felt drawn to read it again at 23, just after graduating from college and beginning my adult life as an entry level peon in a gleaming glass building in The Big City. I would say my relationship to the novel was superficial at this stage in my life. I was drawn to Esther’s perceptive nature and her sinister observations of the people around her, but was also swept away by her glitzy 1950s New York City womens’ magazine life and all the advantages that came with it. I thought her breakdown was an interesting and important representation of mental illness, but I didn’t really identify with it.

At 39, I felt called to read the novel again. I don’t think I’ve ever identified more with a book in my life.

It’s funny how different parts of The Bell Jar have come to manifest in my life over the years. The summer after I read it for the first time my father died suddenly of a massive heart attack in the middle of the night. Like Esther and Plath, I was now fatherless. And as I entered my 30s, I found myself working for a womens’ website focused on fashion, beauty and celebrity. I don’t think I thought consciously about it at the time, but I was suddenly subject to all the perks that came with Esther’s summer internship at Ladies’ Day. Glamorous parties, the occasional trip to New York where I was put up at a posh hotel, and a bottomless pile of covetable swag freshly replenished on the kitchen table each day that came to us from brands who hoped our editors would write about them in exchange for free advertising. I enjoyed these privileges. And I enjoyed that I had finally landed a job that was creatively rewarding. I worked like mad to make sure I kept it. And like so many of the young, enthusiastic, and hungry, I was perfectly happy to do so. Until it began to hurt.

This was the point at which I first began to sow the seeds of burnout. The fruits of their harvest would lead to a series of mental breakdowns that vined their way through my 30s, and eventually to the discovery that like Esther and Plath, I was bipolar.

By the time I quit my antidepressants cold turkey, I had been sowing those seeds for a number of years, and was chronically stressed and exhausted. I had a different job at that point, and was working as a video editor in a busy newsroom. I functioned well enough for the first few months without medication, and then my cat died.

This is when I began to cry at work a lot. Not just for the first few weeks after she died. For months. At first the tears were triggered directly by thoughts of my cat and all the guilt and sadness I felt about her death, but then the tears started to come for seemingly no reason. In boardroom meetings. In front of the water cooler. During reviews of my video edits with producers. Sometimes the tears were easy to conceal, and sometimes they were embarrassing, convulsive sobs that would send me running from the room, ashamed and in shock as to what had come over me. While in the grip of the worst crying spell that had hit me so far, I ran from the office, called my general practitioner, and informed the receptionist as best I could through chattering teeth and hiccuped speech that I thought I was having a mental breakdown and wanted to be placed on medication as soon as possible. Needless to say, the scene in which Esther doesn’t want to have her photo taken at work because she knows she’s going to cry has new poignance for me.

I was off from work for a few weeks per the recommendation of my therapist. She and my general practitioner thought I should be placed on Wellbutrin, something I had never tried before. I was still uncomfortable with medication and all of its synthetic, chemical defilement, but I simply could not continue to feel as terrible as I felt, so I let it go.

It was also around this time that I stopped being able to shit. I began to have digestive issues from overwork at my previous very demanding job, and now that I had been at very demanding job #2 for a few years, the digestive issues had reached their apex. At best, I would produce a small cocoa puff of a bowel movement every one to two weeks, and that was it. This is what sent me to the naturopath and her adaptogens, which, in concert with the Wellbutrin, fried my brain over the course of the next 6 months.

I loved my naturopath and trusted her completely. Although I sought her out to address digestive issues, she said she could treat me for my depression and fatigue too, and it would all be natural. I relished the idea of counter-balancing all the noxious chemical crap that was flowing through my system via the Wellbutrin with her healing herbs, minerals, and adaptogens. According to her, I was in “Stage 3 Adrenal Fatigue.” She piled on neurotransmitter and endocrine system stimulants to kick me out of it.

Stimulants are risky business for people with a bipolar vulnerability, and in addition to the natural stimulants, I was on Wellbutrin. Wellbutrin is often referred to as “the antidepressant . . . with a kick!” It’s notoriously horrible for bipolar people because it’s revving effect often triggers what is called “rapid cycling.” In short, rapid cycling is the process in which one fluctuates between extremely high moods to extremely low moods. The highs and lows can last for a period of months or weeks. At the end of my 6 months of working with the naturopath, when I was on her highest dose of stimulating herbs, amino acids, and minerals, I was rapid cycling several times a day.

My low periods were like out of body experiences. The depression was so heavy it felt like something else took over my body, and whatever that thing was, it wanted me to be horizontal. Working late in the evening before my last day of work, it animated my body right out of my chair and onto the floor, where I lay in front of my desk, unable to move. Witnessing this strange behavior, my coworkers began to ask if I was OK. I mumbled something like, “I’m just so tired,” as quiet tears flowed down my cheeks.

I was not sleeping at this point. When I say I was not sleeping, I don’t mean sleeping badly, but catching a few odd hours here and there. I mean literally not sleeping. It had been a few weeks, and I had been in touch with the naturopath about it. She had recently given me a new tincture of herbs, heavy in St John’s wort, which I was to take 3 times a day. Every time I took it, the depression lifted, and I was filled with a euphoric surge of energy that was a welcome change from my zombie-like fatigue, until it began to feel terrifying. Too good. So good it was scary. Kind of like when you’re falling down a rollercoaster and you get that stomach tickle that’s so intense you have to scream, except it lasts for 3 hours instead of 3 seconds, and there’s no lap bar to hold on to. This would play out for a few hours, and then I would fall back into heavy depression. It was during this time that the naturopath made the suggestion that I might be bipolar.

I was shocked. Me? Bipolar? How? I’d been in and out of psychotherapy since I was 21 and no one had ever made this observation.

She proceeded to gently inform me about the symptoms of bipolar type II disorder, a variety of bipolar disorder I’d never heard of. It’s characterized more by depression than mania, and the depression tends to be very severe and often physical. Depressive episodes are followed by euphoric periods of hypomania, but don’t extend into full blown mania. She wanted me to make an appointment with a psychiatrist to be evaluated. If I was bipolar, she would not continue to treat me. She did not tell me to stop taking the tincture heavy in St. John’s wort.

I felt a horrible sense of doom. If I was indeed bipolar, the only treatments I was aware of were Lithium and electroconvulsive therapy. I could not go on feeling this way. But I could not possibly put Lithium into my glowing green smoothie body. And my beloved naturopath had informed me that she was going to abandon me. My hopelessness had reached new depths.

When I checked in with her about my recent tearful collapse on to the floor at work and my ongoing insomnia, she said that that evening, I should try out a new, natural remedy to help me sleep, called 5-HTP.

The night of the 5-HTP was the worst night so far. I lay in bed, hoping to sleep, but I felt like my heart was beating so fast I was going to die. It frightened me, and I sat up in bed in an attempt to gain some measure of control. Perhaps it was paranoia brought on by the 5-HTP, but suddenly I was suspicious of this woman who I had trusted so completely. I began to google about Bipolar disorder, 5-HTP, and St. John’s wort. You don’t have to dig very deep into the search results to discover that these supplements are akin to poison for someone with a bipolar vulnerability.

I was furious. She and I had been in communication about the possibility of my being bipolar II for a few weeks, during which she had not told me to stop taking the St. John’s wort, and then she proceeded to recommend the addition of 5-HTP. Moreover, in looking over our previous email communications, it became clear that my bipolar II symptoms had been presenting for months. This woman was a professional with a degree in naturopathic medicine who made a colossal fuck up that could have been corrected by a bit of light googling. This is where the danger of influencers and wellness gurus causally recommending natural supplementation lies.

By the time the sun came up, I had flipped back into depression. I made my way to work across the city, each step slow, leaden, and requiring Herculean effort, while senior citizens with mobility issues passed me up on the street. Eventually, I arrived at work, took my seat, and began to robotically go through the motions of my job. But I could not stop crying. They were not loud, hysterical sobs. They were soft, quiet tears, but they were steady, and the woman who sat next to me had noticed. She suggested we go for a walk. She was gentle and kind, and as we moved slowly around the block, I was given instructions. She told me I was going take some time away from work, and coached me on what I would say to my supervisors when I got back to the office. I was to tell them that I was experiencing some health issues that were very overwhelming, I needed to take some time off to get them in order, and I didn’t know how long that would be.

A few days later I had my first psychiatrist appointment. By our second meeting, she had diagnosed me as bipolar II, and instructed me to stop the Wellbutrin and all herbs and supplements (she was quite horrified when she saw the list of everything the naturopath had me on). I had a prescription to fill for Seroquel and Lamictal. Seroquel to help me sleep (I still was not sleeping at this point), and Lamictal, an anticonvulsant traditionally used to treat epilepsy, to stabilize my moods and lift my depression.

I was grateful that the side effects associated with these meds were not as severe as the side effects associated with other bipolar meds, but I still feared I would be struck down by every single one of them. I was particularly terrified of the rash associated with Lamictal, because if I developed the rash, I would no longer be allowed to take Lamictal. After Lamictal, the only treatment options I was aware of were scary drugs that left you fat and exhausted and made your hair fall out.

I never got the rash.

I never developed any of the side effects.

I have now been on this medication for almost 4 years, and I am thriving.

Per the request of my psychiatrist, I get my kidneys, liver, thyroid, and cholesterol checked every year to make sure my body is tolerating the medication. My numbers are outstanding.

I share my story because I hope it will reach other health conscious people who are afraid of medication. Trying to treat my mental illness naturally was destroying my life. Just because you take medication doesn’t mean you’re going to nuke your system, and if you don’t know what you’re doing with natural medicine, you just might nuke your brain. I love my toxic, impure, chemical medication, and I will never stop taking it again.

My heart breaks for Sylvia Plath. I see her as a woman whose gifts were unappreciated, who struggled to find the time to make her art under the weight of motherhood and the vampiric shadow of her husband, and who, in her lifetime, received little praise or encouragement from critics for her writing. The Bell Jar was published to lukewarm reviews only one month before she died by her own hand.

Sylvia, if the light of the soul extends beyond death, may the universe magically relay that your writing has pierced the hearts of millions, your works are considered classics, you are a goddess of letters, and your novel validates my soul beyond expression.

ON TO THE CRAB-STUFFED AVOCADOS

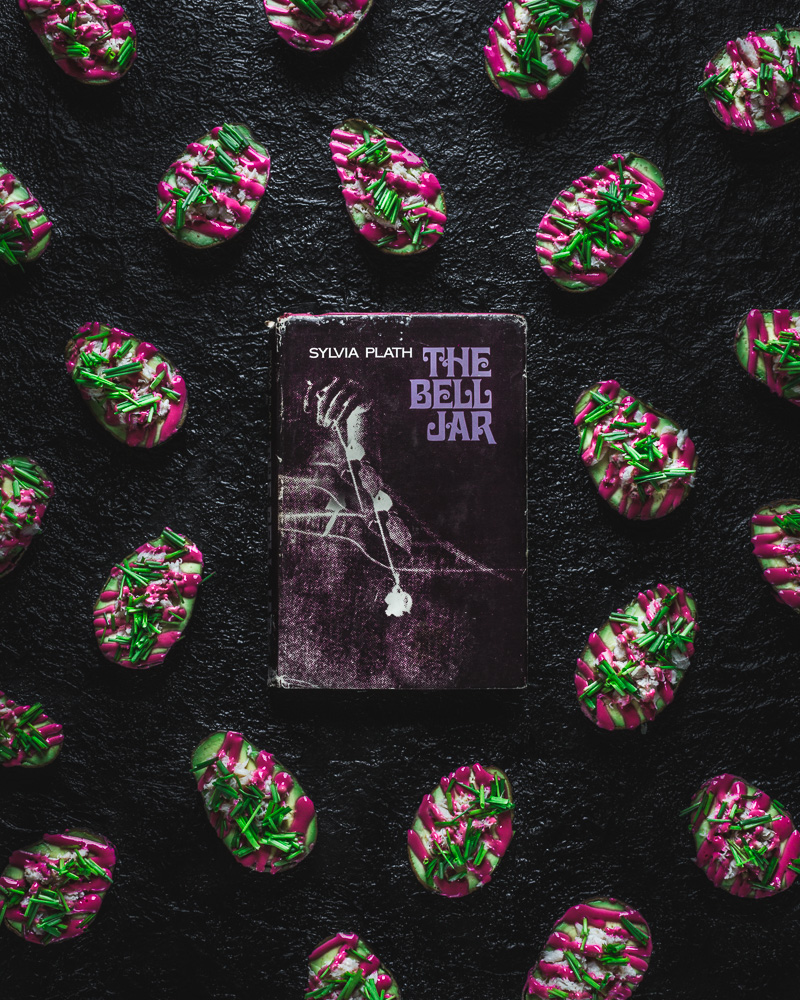

“Arrayed on the Ladies’ Day banquet table were yellow-green avocado pear halves stuffed with crabmeat and mayonnaise, and platters of rare roast beef and cold chicken, and every so often a cut-glass bowl heaped with black caviar. I hadn’t had time to eat any breakfast at the hotel cafeteria that morning, except for a cup of overstewed coffee so bitter it made my nose curl, and I was starving.“

The Bell Jar, Sylvia Plath

Over my three decennial readings of The Bell Jar, the binge eating scene in which Esther shamelessly gorges herself on a mid-century Manhattan spread of caviar, cold chicken, and crab-stuffed avocados at the Ladies’ Day luncheon has always stayed with me. I love the unabashed pleasure she takes from her food, and how she strategically positions herself between two bowls of caviar set out to feed four people so that she can consume all of it. But poor Esther is rather disappointed in the crab-stuffed avocados, and finds them bland. She recalls sharing avocados with her grandfather, and a sauce of grape jelly and french dressing that he heated in a saucepan and tucked into the pit in the avocado left by the stone. I’ve done my best to remedy Esther’s longing by creating a garnet-colored sauce of my own to dress the crab. It’s a delicious puree of mango, raw beetroot, lemon, and olive oil that delivers a pop of color bold enough to be a part of 1950s technicolor magazine spread.

RECIPE NOTES

For the dressing, be sure to use raw beetroot, not cooked, or the sauce will be sickly sweet.

You’ll need a powerful blender such as a Vitamix to get a good, creamy emulsion without chunks, but if you don’t have one, just run your blender for a long time and give it breaks in between to avoid overheating.

You’ll need a squeezable condiment bottle to pipe the dressing onto the avocado halves. If you don’t have one, you can use a narrow spoon, but it will be more difficult and yield a different effect.

The amount of meat referenced in the recipe is what you can pick out of two crabs weighing 2 lbs each (907g) – i.e. that’s how much the crabs should weigh with their shells on.

RECIPE: CRAB-STUFFED AVOCADOS WITH MANGO, BEETROOT AND LEMON DRESSING

Makes 18 crab stuffed avocado halves

Prep time: 30 minutes

INGREDIENTS

1 cup (237 mL) frozen mango chunks

1/2 cup (118 mL) freshly grated, raw beetroot

2 tbsp freshly squeezed lemon juice

Scant 1/4 cup (59 mL) water

1/2 cup (118 mL) olive oil

1/4 tsp salt

9 avocados

12.75 oz (360g) crab meat (this is the approximate amount of meat that can be picked from two crabs weighing 2 lbs each – a.k.a. 907g)

Large bunch of scallions

INSTRUCTIONS

Make the dressing. Place frozen mango chunks, freshly grated beetroot, lemon juice, water, and olive oil in a powerful blender and run on high for 2 minutes. Transfer contents to a squeezable condiment bottle.

Prep the avocados by slicing in half and removing the stone. Slice a small amount off the curved bottom of each avocado half so that it will sit evenly on a serving dish without wobbling.

Stuff the avocado pit holes with crab meat. Be generous, and let the meat spill beyond the pit hole and across the pale green flesh of the avocado.

Grab your squeezable condiment bottle full of mango, beetroot and lemon dressing, and pipe artsy zigzags across your avocado halves. Finish with a scattering of freshly minced chives, and if you’ve been stable on your meds, perhaps a vodka martini on the side. Don’t forget to make a toast to Sylvia.