By the time I was deep into writing this piece, memories I had repressed surrounding my father’s death began to surface, usually as I was falling asleep. I had forgotten his funeral was open casket, until an image floated into my mind as I was drifting off.

I screamed.

It was not the image of his dead body that made me cry out. It was the gaudy flower arrangement beside his casket, hung with a beauty pageant sash that read:

“Loving Father, Devoted Husband.”

Words that provided some small comfort on that day now seemed to proclaim his cause of death: a man who died in service to his family, a man whose devotion to an abusive spouse killed him, a beautiful man whose essence was traded for things, the father I lost to consumerism when I was 16.

When I started this project, I thought it was going to be about exploring my love of industrial ruins, thinking I might be able to connect them to my love of industrial music. By the time I finished, I realized I was looking for my father.

I saw my first industrial ruins 16 years after he died. My husband and I had set off to explore San Francisco’s Dogpatch neighborhood, where we stumbled across the majestic remains of Pier 70: a collection of rusting cranes and deteriorating 19th century factories at the edge of the Bay, a ghost town of heavy industry that occupied as much space as a large village. It was a freezing day, clear and bright. The winds were blowing fast and hard, rattling the rusty corrugated metal strips that lined the warehouses, hissing through the jagged panes of broken steel sash windows, like the ghosts of all its long gone workers, coming to say hello.

We searched the boarded up windows for places where the planks had fallen away, and pressed our faces close, straining for a glimpse of what lay inside. The interiors were cavernous, great halls. Skylights spanned the length of rooftops. Massive steel girders soared beneath them, as regal as the flying buttresses of cathedrals. We were taunted by the site of huge, mysterious machines for which we had no explanation. I longed desperately to go inside.

When I returned home, I went online and learned Pier 70 is regarded as the best-preserved 19th century industrial complex west of the Mississippi. I found photos of its workers bronze casting giant ship propellers above huge steaming cauldrons and thought they were sorcerers. Their work was dangerous and I romanticized it: toxic fumes, explosive gases, high voltages, working from heights – the antithesis of office life. The experience ignited a passion, curiosity, and respect for the blue collar industrial work history of the United States I’d never had before.

I realized my father had been a part of the blue collar industrial work history of the Bay Area.

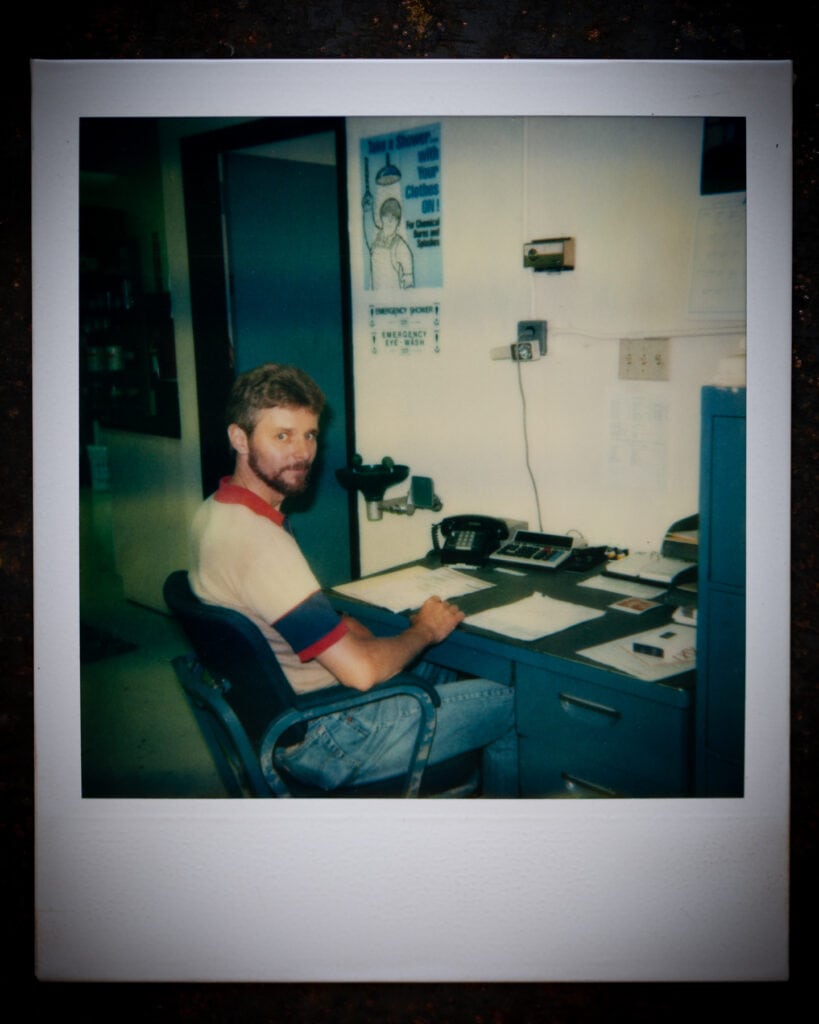

When he finished high school he married my mother and got a job at Hunt’s Cannery, where he worked the graveyard shift. He went on to work at the GM plant in Fremont, where he built car seats, and then at Dexter Midland in Hayward, where he eventually became a foreman.

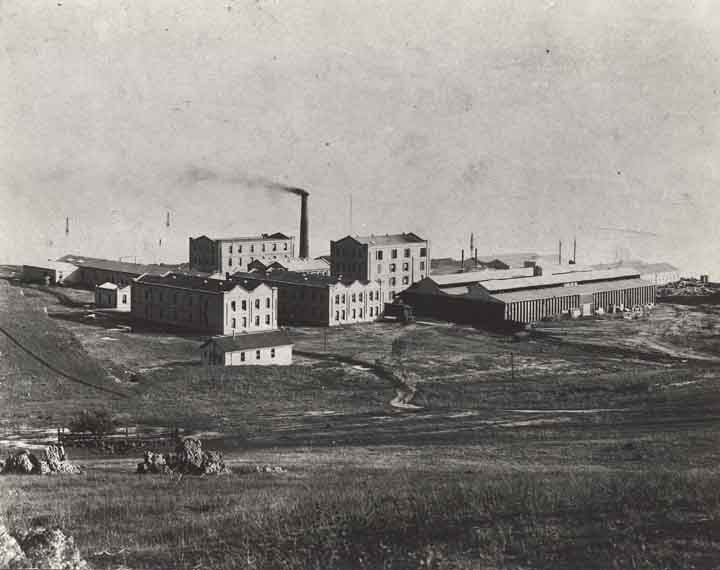

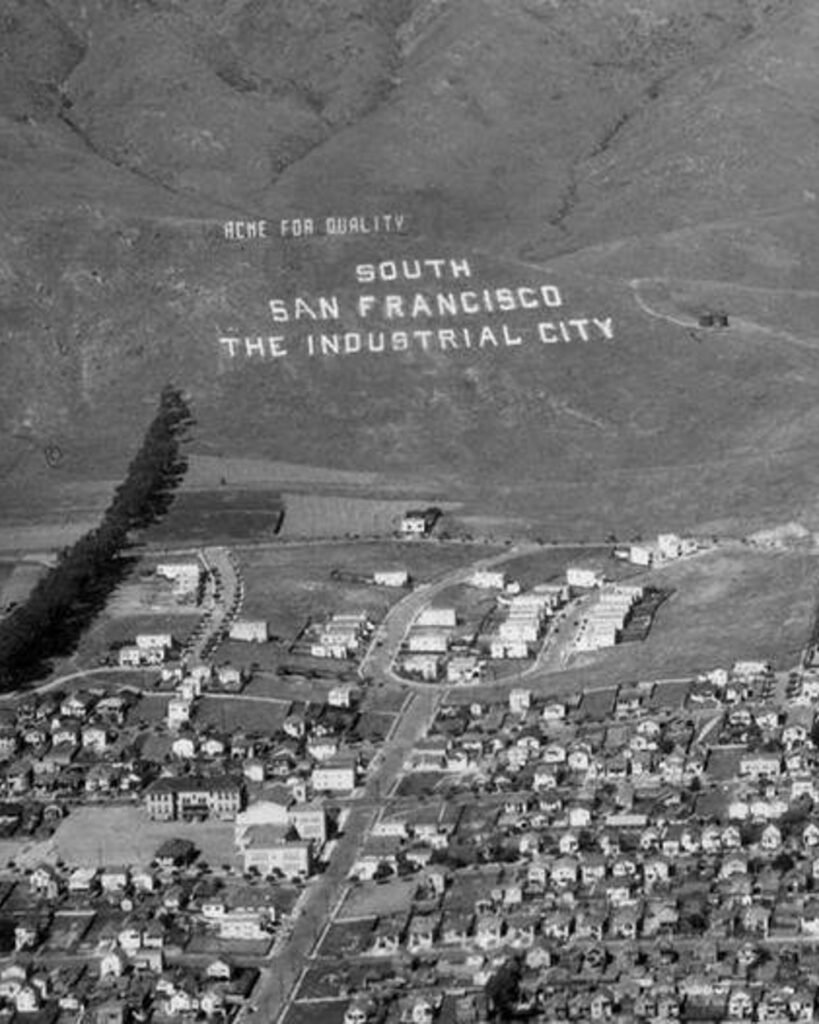

By the time I was old enough to know what he was doing for work, he was working in South San Francisco, “The Industrial City,” as proudly proclaimed across the hillside in 65-foot tall letters, like the Hollywood sign. He was a manager at the Fuller O’Brien paint factory there. I didn’t really know what he did, but I liked the Fuller O’Brien logo and thought he worked at “the happy rainbow paint factory.” At the end of 1st grade, we had an assignment to draw placemats to give to our fathers for Father’s Day. I drew an alternating pattern of hearts and Fuller O’Brien paint cans all along the border, writing out the name in full each time. I loved to draw and paint and color; somehow his job, though mysterious to me, was associated with that. I also knew his job had made him a hero: he once crawled into a giant tank to save a man from a chemical fire that ignited while he was cleaning it. After rescuing the man, he returned to the tank to put the fire out himself. The company showed their appreciation by giving him a watch with the Fuller O’Brien logo on its face. As a child, I thought it was a medal of honor.

I began to wonder if the factory where he worked had been like the structures at Pier 70. I have a hazy memory of stopping by when I was young: me sitting in a parked car, the door ajar, a vague impression of a tall brick building in the late afternoon sun, sparkling water in the distance. I knew the factory was old: old enough to have a machinist ghost who’d died in an industrial accident and sometimes made an appearance during the graveyard shift – the workers would tell my father when they saw him, and he’d share the ghost stories with us when he got home over our family dinner.

I wanted to see the factory now, and understand how it worked. I wanted to see the tank farms, the ball mills, and ask all the geeky questions.

I phoned my sister and asked her if she wanted to go. She informed me that it had been torn down, and the land had been used to build a parking garage for Genentech.

I was disappointed, but I still wanted to know what the factory looked like. I did some googling but surprisingly could not come up with any images.

I had so many questions, but it was too late.

PEELING THE BLISTERS OFF A WORKING HAND

My first visit to Pier 70 was at age 32. I am 41 now, 2 years shy of the age my father died. Since then, I have experienced the weight of modern American adult life, and it has hardened me.

It has also changed the way I understand my father’s death.

I was a video editor working for different news outlets producing content for social media. The material was enriching, but the hours were long, the deadlines were intense, the need for output was constant, and the culture of overwork was toxic. I was chronically exhausted and could barely get out of bed most weekends. I had no energy left to give to myself. I had no energy left to give to anyone or anything.

What little energy I had, I gave to my job.

The pressure to rush contaminated all areas of my life. I developed a digestive disorder, an eating disorder, major depressive disorder, and was in constant pain from excessive computer use without enough breaks. I was finally diagnosed as bipolar, and shortly after that, a repetitive strain injury took me out of work for 8 months. It would be 2 years before my body healed sufficiently to work full time.

During my leave from work, I would take long walks while listening to music. Sometimes I would listen to my father’s music – artists like Leonard Cohen and Pink Floyd. And sometimes I would listen to my own music – often the old school, industrial jams I’d loved as a teen. One morning, Spotify’s algorithm offered me Ministry’s “All Day,” from their album, Twitch. I hadn’t heard the song since high school, and chuckled at the memory of hearing it for the first time in my sister’s car, cruising down the highway while spinning a freshly purchased Cleopatra Records compilation we’d split the cost of back in 1994. We couldn’t believe it was Ministry and laughed about how we thought they sounded like Depeche Mode. I thought it was a fun industrial pop song, but never took it very seriously. Eventually I forgot about it. Until that morning.

I heard the song anew. Samples of a military crew chanting the orders of a drill sergeant juxtaposed with lyrics about overwork and exploitation climaxing in a percussive loop made of Al Jorgensen’s gasping, panting, exhausted breaths validated what I had experienced. I felt those breaths cathartically, because I had been running the same, pointless race to feed the machine.

I realized my father had been running that race too, and I thought of the last, ragged, rasping breaths I heard him take, as he died of a heart attack in the middle of the night.

But my father didn’t struggle because his job was exploitative. He struggled because his home life was.

WELCOME TO THE MACHINE

My father was brought up in the 50s and 60s, a time when American men were taught that their mission in life was to fill the role of “provider.” He’d seen that dynamic play out in his childhood home: his father provided for his family with the gas station he leased. But he’d also seen how things played out when the life the man provided wasn’t good enough. His father’s status as a blue collar laborer displeased his mother, who felt she deserved to live the life of a higher class. She was never satisfied, and frequently made it known. There was conflict, and their arguments were heightened by drugs and alcohol. These experiences colored my father’s childhood and likely informed his ideas of what marriage looked like.

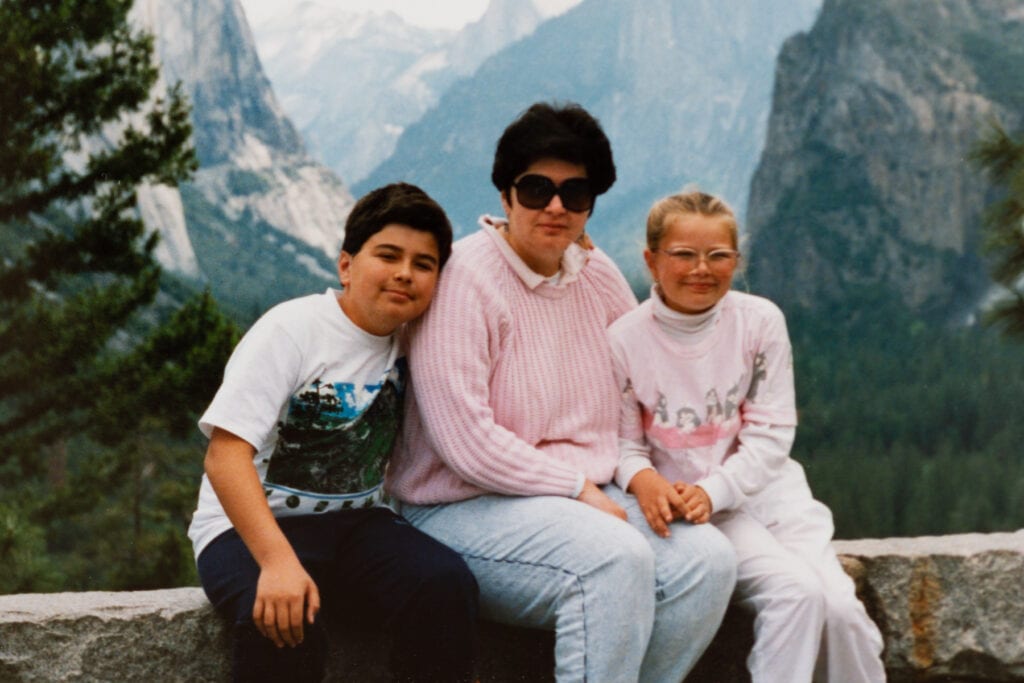

In the 1980s, my family lived in San Leandro, which was directly across the Bay from the Fuller O’Brien factory where my father worked, until I was 10. He had a commute, but it was manageable: about 45 minutes each way, split with a carpool of friends to lighten the burden. Every night when he came home, I would run to him and cry out “Dirty Dancing!” and he would try to lift me over his head like Jennifer Grey.

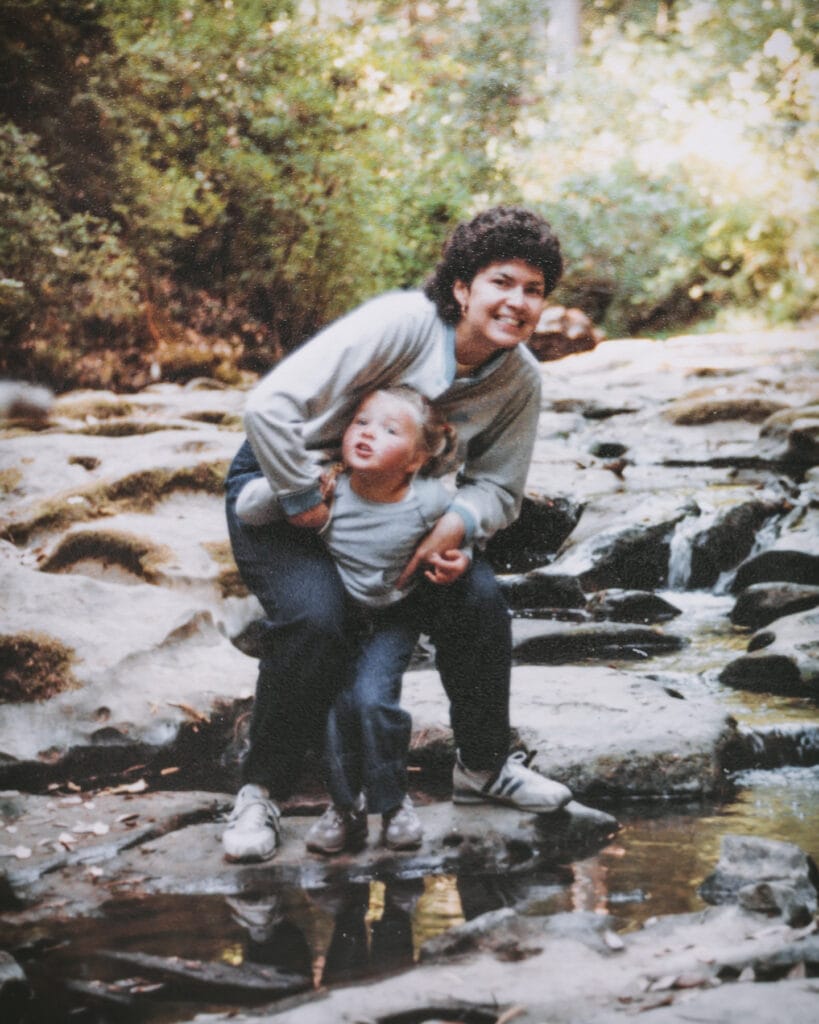

My mom worked too, doing admin in a court clerk’s office. Times were different then: houses were smaller and more affordable. Together my parents, who were only in their 20s, had managed to use their modest, working class income to achieve The American Dream: two kids and a house. My sister and I loved living there and we loved our neighborhood. It was surrounded by creeks and canals and was close to the Bay, and my father often took us to ride bikes out to the marshlands to watch the golden hour. He loved his children, and we loved him. He was gentle, patient, and kind, a pillar of stability in our rocky household, which often shook with my mother’s rage.

My mother was a walking time bomb, and had been for as long as I remember. She could be generous and nurturing: she gently combed the tangles from my hair, made me cookies and Halloween costumes, encouraged my artistic side, and always made an effort to learn about whatever I was into so she could share it with me. But she had a capacity for rage and could turn like the flip of the switch.

One of my earliest memories is of her packing a pale blue, hard shell suitcase, throwing her curling iron into it and screaming, “I’m leaving, and I’m never coming back!” I remember the suitcase slamming shut, crying and running after her in my Rainbow Brite nightgown, cheeks hot with tears, as her car peeled out of the driveway, sped down the street, turned the corner, and disappeared. I was young and truly believed she meant it.

I think the pressure of being a working parent was too much for my mother. She was resentful, and taking it out on the family gave her a sense of release. I think she liked to feel she was in control, and using aggression to get her needs met made her feel powerful. I never saw her be physically violent with my father, but she would scream at him, and he would take her bullying quietly. I imagine he did so to diffuse the threat of physical violence to his children, whom she beat.

My sister got it the worst. She was older but also latently transgender: she didn’t realize she was trans until she was 40. Throughout our childhood, her gender nonconformities manifested in ways that 1980s society wasn’t equipped to understand. She was teased at Catholic school for not measuring up to traditional standards of masculinity, and she was teased at home by our mother for being “too sensitive.” She encouraged my sister to use violence against the kids who teased her for not being masculine enough, and chastised her when she didn’t. “You need to haul off and hit them!”

Violence was her preferred method of expression, and she led by example. One evening while our family was enjoying takeout from Round Table Pizza, my mother picked on my sister, accusing her of eating too much. In the 1980s, Round Table cut their slices much thinner than they do now, and they were often like small, narrow triangles.

My sister gently protested, “But I only had 4 pieces…”

My mother threw her plate at my sister’s head.

“You know I hate it when you count food!”

The plate narrowly missed her face, and shattered against the wall.

No one said anything. My sister bent forward and obediently began to pick up the sharp, broken shards of plate, and my father quietly joined her. Trying to defend or comfort my sister would have been seen as an affront to our mother, causing her to become further unhinged.

My mother left the room to retrieve another plate for herself, and then returned, carefree and smiling, as though nothing had happened.

She usually beat us after school, where my strategy became “duck and cover.” She would hold me down, and I would become small and shield my arms over my head while I waited for the rain of blows to end. She generally did it before our father had returned home from work, but sometimes she did it in front of him. I do not recall him trying to stop her. Her beatings were always interspersed with periods of love and laughter and happiness that made things confusing.

What my father did do was try to passively diffuse situations in ways that would pass undetected by her, avoiding offense.

One evening at our local park, we were all together, walking to our car at dusk. Some teenagers near us had just lit the fuse of a giant firework they’d placed in a mounted barbecue at a picnic area we were passing. My sister was lagging behind the family a bit, and remembers the guy who lit the fuse looking directly at her and going, “Watch out! Watch out! Watch out!” as he hurried away.

My sister involuntarily yelped, and ran toward Mommy and Daddy, as any typical child would.

Then the firework went off and made a huge, loud bang, startling her even more. She freaked out and began to cry.

But there was no comfort to be offered to my sister.

Instead, comfort had to be directed to our mother, who was “mortified!” her son had humiliated her by being afraid of “a little firework!”

Our father said only, “That was a barrel bomb.”

She continued to be pissed at my sister for being scared and “mortifying” her as we made our way to the car. It was one of the formative experiences that taught my sister she was a gigantic, perpetually disappointing, utterly inadequate embarrassment.

Our father had to watch her do this to his child. And say nothing. Lest he make the situation worse. His comment about the barrel bomb was likely a subtle way of noting it was not just a “little firework” but actually kind of a gigantic one, and a perfectly legitimate thing to be scared of.

But that’s all he could afford to say.

Shortly before my father died, my sister confronted him about the abuse. She was almost 19 and had come into her power.

She did this whenever they were alone together in the car. It was difficult for him to open up, and her confrontations were generally met with silence and the gentle roar of the road. Our father was very honorable, and was not willing to openly disparage our mother, despite the ways in which she had repeatedly violated our family.

But my sister’s contempt for our mother was in full bloom, and she was determined to make him say something. She charged through, giving specific, concrete, undeniable examples of things she had done to us, and to him. She asked him why he let her do it, why didn’t he stop her from hurting us, and him, when he had to have known it was wrong.

After a long silence, he caved.

“I did try to stop her. I used to try to stop her when you and your sister were very young. And it would make her much more angry when I did. I was afraid she was going to really hurt you guys. So I stopped fighting back against her when she would get angry, and did everything I could to stop it from happening. I did whatever I could to keep her calm.”

My sister was incredibly stunned to hear him say this, and immediately felt guilty about it, like she had pushed him too far, realizing the admission must have been humiliating for him.

But she also had the sense it was a relief for him to say.

As middle-aged adults, my sister and I have struggled to understand why our father didn’t try to divorce our mother and take us away from her. We have come to the conclusion that he believed he had no choice but to stay. Abandonment was our mother’s greatest fear, and the threat of it was her greatest trigger. To propose the idea of a separation would have caused her to become destabilized to a degree we had not yet seen. This was a woman who liked to take off her seatbelt and open the car door as our family sped down the freeway, threatening to throw herself into the road. She once chased my sister around the house with a large kitchen knife. I don’t think our family would have survived a divorce.

If the case went to court, she probably would have denied she abused us. There would have been a risk they would award us to her, and my father would not have been able to protect us anymore. In those days it was far more common for courts to give sole custody to the mother, and a lot less common for them to recognize that women could abuse men.

I also think he took their marital vows seriously. They had been in love once, and he remained devoted to her despite her repeated violations. I think there was a part of him that still loved her, just as there is still a part of me that loves her, despite everything she’s done.

KEEPING HER CALM

Around 1989, my mother began to desire a larger, more glamorous home. Like my father’s mother, my mother believed she “deserved to have things and live a life of a certain standard.” She wanted a big, beautiful house, and she wanted it to be furnished with brand new things.

I have hazy memories of my parents arguing about this. According to my mother, our San Leandro house was “just too small!”

It had 3 bedrooms, 2 bathrooms, a family room, a living room, a dining room, and a kitchen dining area too. It had a fireplace, a playroom, and a big backyard where my father had built a deck and installed a swingset. It even had an atrium.

But when my mother wants something she wields her anger like a superpower. If you try to reason with her, she will only become more angry. So you learn not to express your thoughts and feelings.

But eventually you can’t swallow them anymore. One of them escapes, bubbles up, becomes external. You try to get through to her, help her to see the nature of reality.

She rages.

And then she launches a Starship Enterprise-sized pity party.

And you fall for it.

It’s your fault. Look how upset you made her. Look how sad you made her. Look how you hurt her. You feel so terrible. Moreover, YOU are terrible.

You are a terrible person.

You have to make it better. Not only to make her feel better, but to feel better about yourself. Your feelings and the ways in which her anger has made you vulnerable cease to matter. It is only her feelings you are concerned with now. What she wants becomes what you want, as your mind grows cloudy, and you forget what you believe in.

This is what dealing with my mother feels like.

And this is how she gets her way.

Our family began to spend weekends visiting model homes in faraway lands, where big houses cost less. We did this for about a year. I suspect my father was trying to draw it out for as long as possible. My sister and I were perfectly happy at our house in San Leandro, and neither of us had a desire to leave, but we went along with what our parents seemed to want to do, and had fun with it. We enjoyed listening to music on the long car rides, and were swept away by the beauty of the model homes, “oohing” and “aahing” over things we’d never seen before, like walk-in closets, daybeds, and giant bathtubs with fireplaces in front of them.

It pains me to imagine what it was like for my father to hear his children make these sounds, as the “I am a man and I must provide for my family” narrative played out in his head.

We moved to the Central California town of Tracy, where it cost less money to buy a gigantic house. My father’s 45-minute, one-way commute turned into a round-trip commute that often hovered close to 3.5 hours when traffic was bad. Our new home was filled with entirely new things: new couches and tables for the family room, new couches and tables for the living room, new end tables, new kitchen table set, new dining table set, new plates, new glassware, new silverware, gold-plated silverware and fine china for the dining room, new stereo, new TV, new beds, new bedding, custom drapery, custom window fixtures, new lamps, new art, and new “decor” for every room. My Mom was stuck in an uncreative, low-paying office job, and had always dreamed of being an interior decorator. I imagine this binge was her opportunity to express herself.

A year and a half after we moved to Tracy, my parents filed for bankruptcy. I only discovered this a few months ago, when I found a letter hidden in my mother’s garage. They had $30,000 of credit card debt, among other things.

My father’s job at the paint factory wasn’t enough to cover expenses anymore, so he got a paper route too. My sister and I had spent the later part of the ‘80s playing Paperboy on our Apple 2C, a video game in which you throw papers into people’s yards from your bicycle, and sometimes a boxy graphic of a happy dog leaps out to catch it from your hand. It seemed fun that he had a paper route.

The paper route was not like a video game. It was hard.

He woke up at 2:30am. This was after catching about 4.5 hours of sleep, because he usually wasn’t able to get to bed until 10pm. He’d arrive at the Tracy Press, assemble the bundles, and then set off to commute to the nearby San Joaquin Valley towns of Bryon and Discovery Bay, where he made a complicated route down winding country roads to deliver the papers. The roads were dark and often obscured by dense tule fog, which is thickest just before dawn. When he returned home around 4:45am, he would shower, change his clothes, and lay down briefly before making the 140-mile round trip commute to work.

As a child I was oblivious to these details. I did not come to know the realities of his commute and what he did on his paper route until I started working on this project.

My heart breaks to imagine my father pulling his truck to the side of the road, over and over again, reaching out his arms, and endlessly shoving papers into plastic mailbox tubes as he wandered exhausted and alone through the dark night.

He did this for four and a half years.

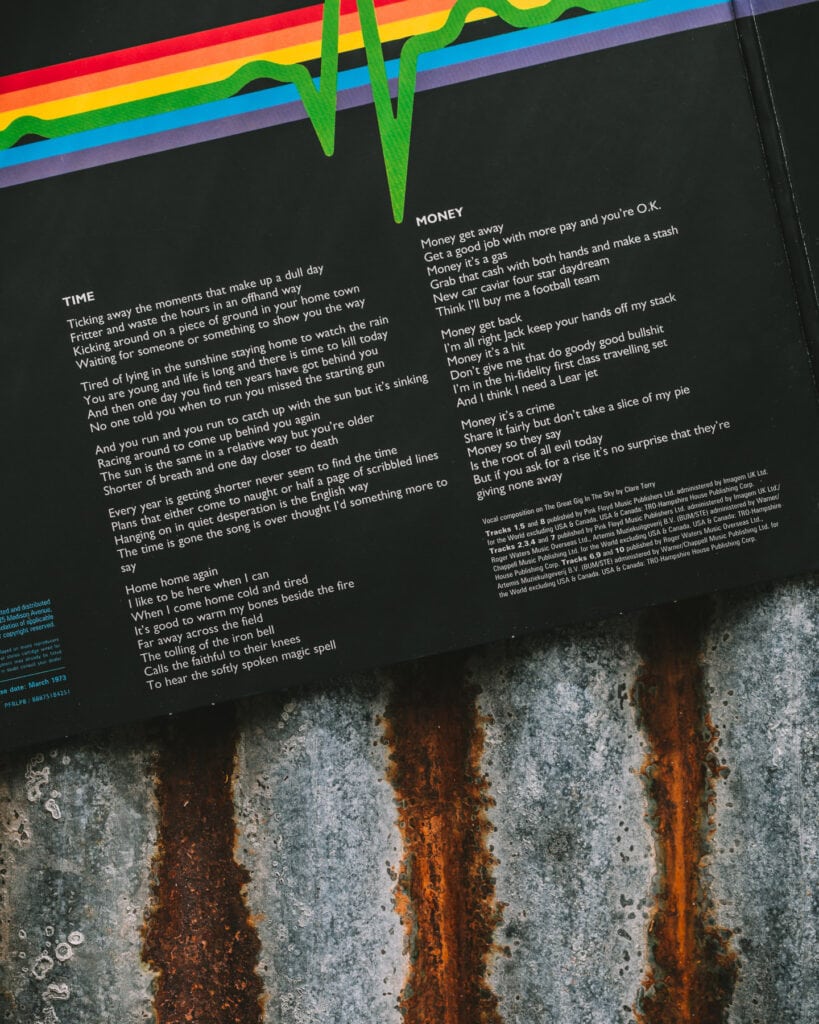

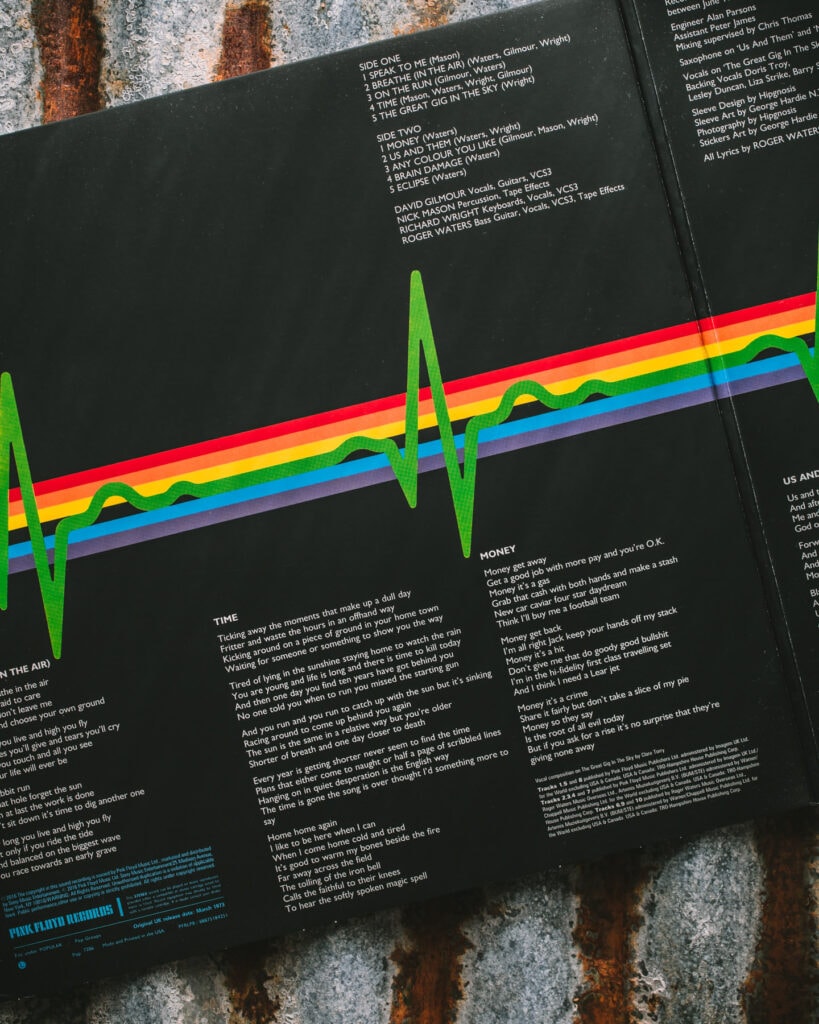

He had a Pink Floyd compilation tape during that time that I know he listened to pretty regularly, A Collection of Great Dance Songs. I listened to the compilation recently in preparation for this project.

The second song on the tape is “Money.”

The idea of him driving that route while listening to that song makes my chest cave in.

Despite all my father was doing to try to give my mother the kind of life she wanted, it seemed like she was always angry with him during this time. On weekends, she’d spend what seemed like hours yelling at him while my sister and I hid in our rooms. He’d taken a new job managing a chemical distribution facility that was even further away than his previous job: about 4 hours round trip when traffic was bad. This was on top of the roughly 2.5 hours he spent in the morning doing his paper route.

But it paid $1100 more per month.

The job seemed to hold more responsibility, and workers would sometimes call our house on weekends and evenings to verify things with him.

My mother would intercept the phone and yell at them too, employing the same threatening tone of voice she used with me and my sister when she wanted to let us to know a beating was coming, strong emphasis on the N, E’s drawn out, hard hit on the D, making it a 3-syllable word:

“You N-EE-D to stop calling here!”

[…or else!!!]

And then she would hang up on them.

She’d then return to yelling at my father, aggressively sharing her thoughts about his job and how he wasn’t doing it the way she thought he should:

“You N-EE-D to tell them this, you N-EE-D to tell them that!”

“ You N-EE-D to do this, you N-EE-D to do that!”

[…or else!!!]

They fought about other things too, and I imagine they were related to the financial pressure created by the house, the bankruptcy, and the various ways in which our family was continuing to live beyond our means. All this was likely amplified by the lower amounts of free time he had available, and the higher levels of stress they were both under (my mother was also commuting to work, though her commute was half as long, and she did not have a second job).

I remember an argument that started in the kitchen before I’d had the opportunity to evacuate, my mother dramatically grasping the kitchen island as though she might collapse, whipping up a batch of fake toddler tears, and crying, “I thought if we had a bigger house we wouldn’t fight as much!!!”

Even as an 11-year-old I was stunned by the absurdity of the premise and knew it was emotionally manipulative bullshit.

Still, I never tried to protect my father from her, and it saddens me to think of it now. Her yelling at him had become so regular it almost felt normal, and her rageful episodes continued to be interspersed with happy events like family trips to the movies, days at the beach, and dinners at our favorite chain restaurants.

I also knew she was not a force to be crossed. She was still in the habit of coming home from work angry and taking it out on me and my sister.

I started to be afraid of our new house. It made me anxious. I was afraid of the walls, the high points where they met the corners of the ceiling. I thought they wanted to smother me, attack me, and I would become restless in my bed at night. One night I had a nightmare so vivid I can still remember it: giant maggots as tall as walls that walked upright, wriggling and squishing their bodies together to form a barrier, squeezing around our San Leandro house and swallowing it whole, while I was trapped in our playroom on a dark and stormy night.

Meanwhile, I was given new clothes to wear all the time. My mother liked me to have them, and I liked receiving them, as any typical teenage girl would. It was one of the ways she showed her love for me when she was in nurturing mode: a lunch date and an afternoon at the mall, which sometimes even included a trip to the jewelry counter. I always had a good time, and was never made to understand that we were living a lifestyle beyond our means, that my father was putting himself through hell to pay off our family’s debt, and that we couldn’t afford these excesses. As an adult, knowing how much things cost and how quickly they all add up, it hurts me to think how the few extra hundred dollars my father made each month on that horrible paper route were wasted on unnecessary fluff, most of which has probably ended up in a landfill.

Several years after my father passed, my mother confided to my sister that she thought the money she earned was her own and that it was her right to spend it however she liked. I think she might have been dimly aware that what she had done was wrong.

Despite the emotional stress of my mother and his grueling work and commute schedule, my father still managed to do it all with serenity and kindness: the pain he endured did not stamp out the love and energy he gave to his children. He took me and my sister to do fun things and made memories with us: we went to the water slides, we went hiking, he made popcorn and watched movies with us. I still remember when we watched Alive together when I was 13. After the plane crashed at the beginning of the film I involuntarily reached out to where he sat next to me on the couch to hold his hand. I held his hand for the remainder of the film, but did not realize it until I looked down as the credits began to roll.

He helped me with my homework and my reading because I was slow. He taught me to appreciate literature, and when I had to read The Grapes of Wrath for school, he taught me to understand the plight of the Dust Bowl migrants, and empathize with them. I thought the book was boring until he brought it to life for me.

On long drives, he would play his Pink Floyd compilation tape for me and my sister, and tell us stories about going to hear them play at various venues in San Francisco in the ’60s, with their dazzling quadraphonic sound system, the likes of which no one had ever seen. He described the immersive sonic experience it created, and what it felt like. We were spellbound.

About a year before he died, he asked us to give him a tape of The Dark Side of the Moon, so he could listen to it while he commuted.

I played “Breathe” at his funeral.

It only hit me some 21 years later that the lyrics describe his life, that the rabbit frantically digging endless holes and tunnels was him, and that the rabbit and his holes are a metaphor for digging your own grave through overwork.

AND BALANCED ON THE BIGGEST WAVE, YOU RACE TOWARDS AN EARLY GRAVE

I have a memory of my father from the Christmas before he died that confused me as a teenager. The Sunday evening before school resumed from Winter Break, I was in my bedroom, which overlooked the street we lived on. I saw my father, who had just finished taking down the Christmas lights, walk across the street, sit down on the curb, and stare at our house in the dark. I could not read his mood, and I watched him for a long time, puzzled. Eventually he sighed in a way that seemed to drag through his entire body, got up, and walked back across the street into our home.

I think he knew that house was burying him alive.

Signs of his deterioration continued to present in the following months, things that seemed “off” to me that I didn’t quite understand. They make sense now.

In early April, he lost his job at the chemical distribution company. I never understood why, and our entire family believed he’d simply been laid off due to restructuring. He was a solid, highly capable worker, and it was a job he had performed well for several years.

25 years later, I found his termination letter in my mother’s garage: he’d been fired. The letter was preceded by a memo laying out performance issues that began to appear in January, not long after I’d witnessed him staring at the house after taking down the Christmas lights. The memo contained a catastrophic laundry list of mistakes he’d made and things he’d failed to do. He was given the opportunity to redeem himself: the company invited him to create an action plan to rectify his failings and discuss it with his superiors.

According to the termination letter that arrived one month later, he did nothing.

My father had done well for his entire career, always steadily advancing. His work ethic was beyond admirable. It was outstanding. He was a gentle, humble, man of honor who knew how to treat people, and was well-liked. It made no sense. I was convinced he’d been framed.

My sister and my husband helped me to understand that the chronic exhaustion under which he’d been operating for years had reached a breaking point, rendering him physically incapable of doing his job. He was like a piece of machinery that had been worked too hard for too long, an old car that could no longer start: he was beginning to malfunction as he reached his expiration date.

Despite the fact that the job loss provided him with an involuntary recovery period, he continued to fade. He was still doing the paper route, and his hair was starting to turn white. Getting up at 2:30 every morning is unnatural, and I imagine he was never able to fall back asleep, even though he had more free time. I think his biorhythms had adapted to his murderous work schedule and he could not shake the pattern.

I recall a weekday my sister and I both had off from school during that time. We had gone to Berkeley for a day of people watching, window shopping and record crate digging on Telegraph Avenue. When we returned home around 4pm, we were stunned by the sight of our father, framed by the doorway to the master bedroom and the archway to the master bathroom that lay beyond, lying in the bathtub, dull-eyed and sunken, in a posture not unlike The Death of Marat, the 1793 painting that depicts murdered French revolutionary leader Jean-Paul Marat, dead in his bathtub. He was so out of it he hadn’t noticed us come home. I don’t remember many details after that. I think my sister and I said something like, “Hi, sorry…” and closed the double doors to the master bedroom so he could have some privacy. I remember feeling disturbed in the same way I’d been by the sight of him on the sidewalk after Christmas.

He found another job about 6 weeks after being fired, this time in Hayward, working for a wax manufacturing company. It was a much better commute: about an hour each way. He had a bit more time in the mornings, and my heart warms at the memory of him, 5 days before he died, running up the stairs, kneeling over my bed, and smoothing the hair back from my face, as I awoke to the sight of him, full of love, shining down on me, brighter than the sun. He wanted to let me know that Tori Amos was doing a live interview on NPR. She’d come on the air as he’d set off to commute, and returned because he knew how much I loved her.

But he was still fading.

Not long after my father started his new job, my mother began to tell my sister, “Your father is tired. You need to help him.”

My sister had just about wrapped up her first year of college, and would have the summer off before the next school year began. She worked full-time at a cafe throughout her first year, and she would continue to work full-time at the cafe over the summer. But as the older sibling, and the only sibling who knew how to drive, she was to start accompanying our father on the paper route. The goal was for her to learn the route, and eventually relieve him of it. It was complex and would take practice to memorize before she could do it on her own.

The fact my father was ailing and needed help was concealed from me. I knew my sister went with him on the route sometimes, but I thought it was just for fun and the sake of hanging out. She was a night owl and sometimes stayed up till 4am.

Still, it comforts me to think that my sister and our father had a few weeks of time together to talk and bond while she learned the route, and that her presence must have brought him some happiness on that horrible task. By the time our father died, she had learned the route and they were sharing the responsibility by trading off days: my sister did it sometimes, my father did it sometimes.

But it was too late.

On July 17, 1996, around 1:30am, about an hour shy of when he would have been waking up to do his paper route, my father died. He was 43 years old.

I was up late reading when I began to hear strange sounds drifting down the hallway from my parents’ bedroom: long, snore-like rasps, followed by snagging, wet gurgles.

I shot upright in bed.

And then I heard my mother scream my father’s name.

I leapt out of bed and ran down the hall as their bedroom light switched on. When I got there, he was unconscious.

I called 9-1-1 while my sister tried to give him mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. She had no idea what she was doing. Her only training was the Punky Brewster episode where Cherie gets trapped in a refrigerator during a game of hide and seek. She breathed into him four times, then paused, like the Punky Brewster episode had taught her to do.

My father gurgled it all up.

It was like all the air she’d tried to push into his lungs just flowed back out of him, mixing with the fluids in which he’d already drowned.

She tried again a few more times, and got the same result each time. And then she stopped trying.

The fire department came, and later, an ambulance. I watched them do CPR and use the defibrillator, as his skin began to turn blue. They took him to the emergency room, and we followed along in our car. Nothing helped. The heart attack was so massive he died almost instantly.

After my father died, my mother filed for bankruptcy again. We stayed in our giant house until it was foreclosed on, and then we moved into a small duplex rental on the other side of town.

My father’s grave had no headstone for 5 years because we couldn’t afford one.

WISH YOU WERE HERE

In the spring of 2021, I go to Pier 70 more frequently than I ever have. I stand before its grand industrial cathedrals, structures made of brick and steel that were once so strong. They are wilting now, made brittle and frail from time and neglect and the corrosive salt air of the Bay. The area is being redeveloped. I don’t know how much longer they will be permitted to remain, and as I look at them, I feel an ache.

I continue to wonder what the Fuller O’Brien paint factory where my father worked was like.

The happy rainbow paint factory.

A week before my 41st birthday, I use Google to search for an image of the factory again, right before I go to sleep. It is a supermoon, and light spills past the drawn curtains, illuminating the room.

An image finally appears, after all these years.

It is glorious, not just a factory, but a sprawling, 19th century industrial plant at the edge of the Bay, just like Pier 70. Can it really be true that my father worked in the sort of mythic place I’d been romanticizing for the last 9 years?

I cannot sleep that night. I am haunted by memories of my father’s death I had repressed. I see his casket under the hot, noontime sun of late July at the graveyard burial ceremony and worry he is baking inside of it. I wonder about his grave, and what is left of his body. My husband is out of town and I am scared. I keep having to get up to pee, but I am afraid to go to the bathroom. I am afraid the machinist ghost from the graveyard shift at the paint factory will be there, and maybe my father’s ghost will be there too. I make my way to the bathroom with my eyes closed, and keep them shut the whole time, until I get back into bed. Eventually I fall asleep.

The next morning, I sit down at the kitchen table, cradle my phone between my hands, and stare at the small, low resolution photo of the plant again. I surprise myself when I burst into tears.

I thought my father‘s death was something I was over. Something I had processed and neatly filed away for the last 25 years. Something I could talk to people about without getting shaky, something as matter-of-fact and devoid of emotion as telling someone I went to the grocery store.

I shake the tears off and get dressed to take on the day.

My 41st birthday is approaching, and when my husband returns home, he asks me what I want to do. I tell him I want to go to South San Francisco, The Industrial City, to visit the burial ground of my father’s factory. I know it’s gone, but I want to go to where it was. I want to go to the land it occupied, and try to work it out spatially. Was it really there, right on the water, just like Pier 70?

And even though Fuller O’Brien is gone, I hope to find other old factories there. I want to gaze at their beauty and explore their grounds. Surely South San Francisco must have left something behind to honor its legacy as the city of the proletariat and its role in the industrialization of the Bay Area.

My birthday arrives. My husband and I head to Pacifica for crab sandwiches, and then we set off for South San Francisco, in search of industrial ruins.

Everything is gone.

It is no longer “The Industrial City.” It is the biotechnology city. It seems the only evidence of its former life is the grungy hillside sign.

My husband takes me to visit the South San Francisco Historical Society Museum, where they have an exhibit about the Fuller O’Brien plant. There is a giant map on the wall in which the structures of the manufacturing industries that used to occupy the South San Francisco shoreline are illustrated in detail, smokestacks and all. I am awestruck when I see how much of that space was occupied by the Fuller O’Brien plant, which covered all of Point San Bruno. My heart swells with pride for my father, and the history of the lost civilization he played a part in. The exhibit about Fuller O’Brien includes photos from the interiors of some of the buildings at the plant. My desire to have seen the place and gone inside is somewhat fulfilled.

Then my husband takes me to the Genentech Campus, where Fuller O’Brien used to be. I look at the gleaming glass buildings, sleek and modern, and try to work out where the structures of the plant would have been. We discover a path that winds along the campus at the edge of the Bay and we walk it. Wild California poppies sprout up all around us, my father’s favorite. I think about him as I walk the path and feel the wind. It is low tide, and when my husband and I make our way around a turn we are amazed to find ruins along the shoreline that must have been left behind by the demolition crew 28 years ago. Red bricks are everywhere. A giant rusting pillar blooms with color. We find chunks of concrete threaded with rebar. A rotting steel beam. An air vent. I run to them and put my hands on them.

I look up and see snowy egrets, my father’s favorite birds, dancing in the sparkling water that laps the shoreline. I smile and wonder if he knows I am here, and that I am so proud of who he was.

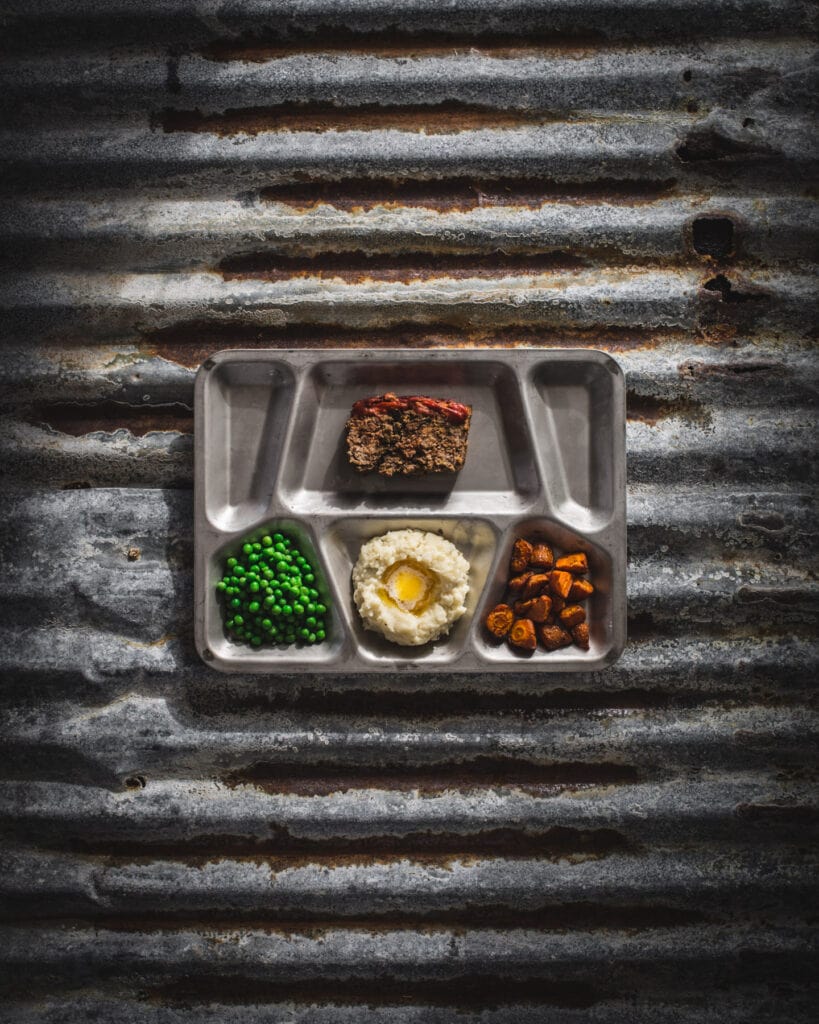

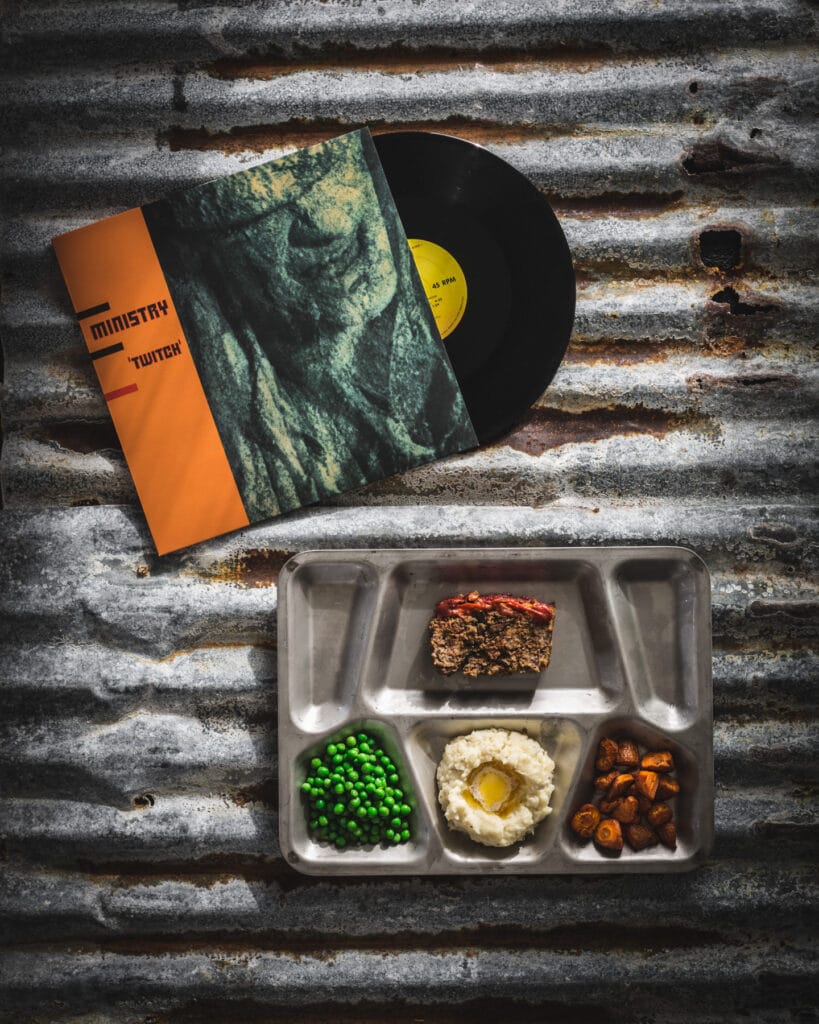

THE FOOD: INDUSTRIAL MEATLOAF

I wanted to make a meal to nourish my father’s spirit, to care for him in the way I was never able to in life, because I was too young, too oblivious, and too unaware of all the ways in which he was suffering. I can see through his eyes now, and know what he must have felt. The reality of his experience has come home to me.

If he were here today, he would be 69. I try to imagine what he would look like as an old man, and as I do so, an image floats into my mind. I see him lying in bed, elevated by pillows, looking up at me with his sweet blue eyes, smiling softly, as I sit beside him. He glows, and light flows out of him, warm as the sun, like the morning he woke me up to let me know Tori was on the radio.

I will beam down at him like that now.

I will set this tray at his bedside, as I bend forward to kiss his forehead, smooth the hair back from his face, take him in my arms, and cradle him. I will witness everything he had to hide. I will hold all that he endured alone and in silence. I will shine for him with all the light of the sun, as I nurse him back to health.

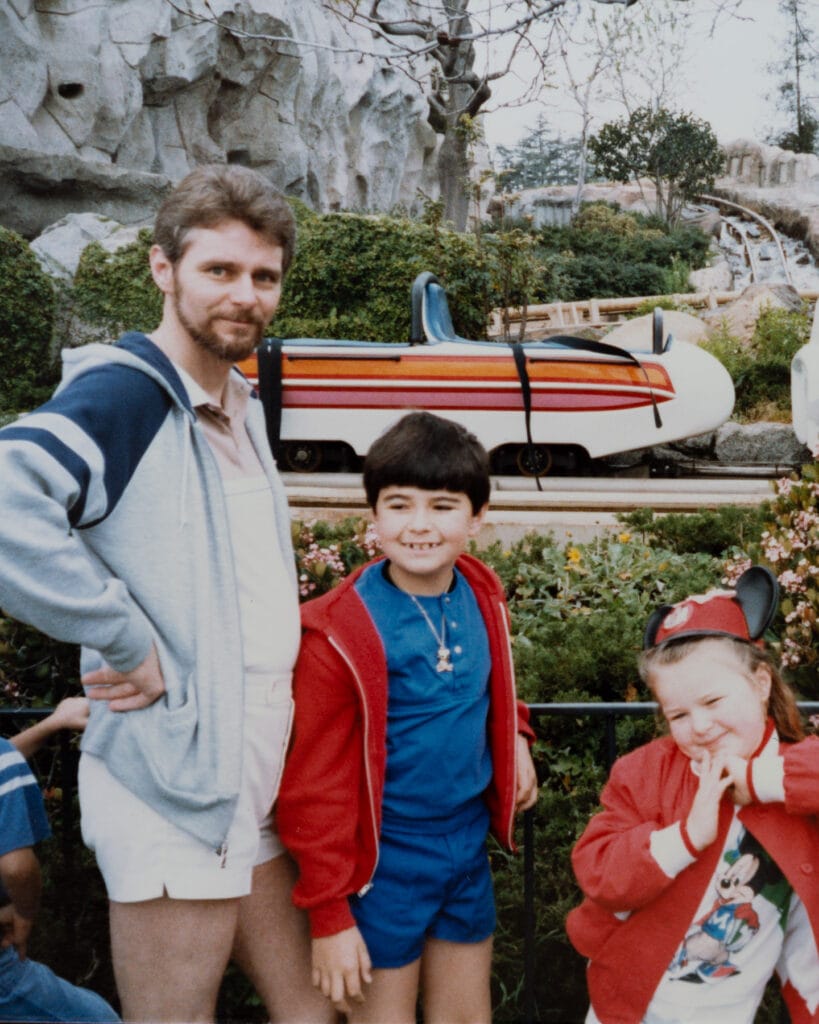

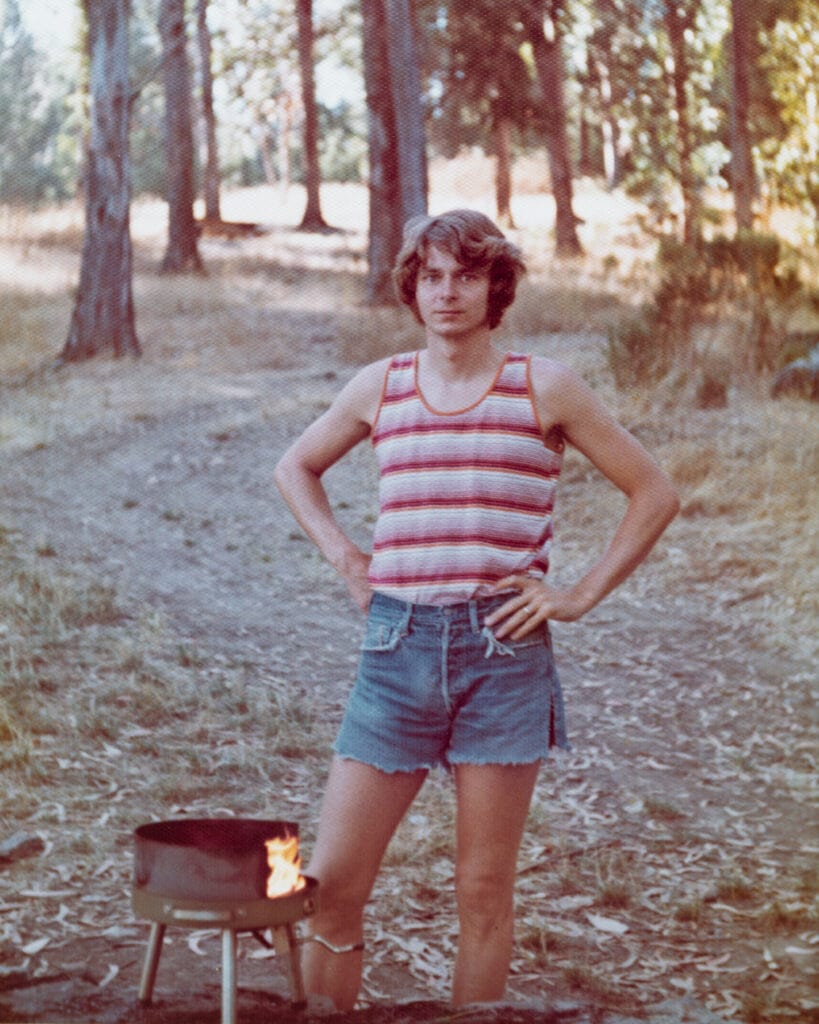

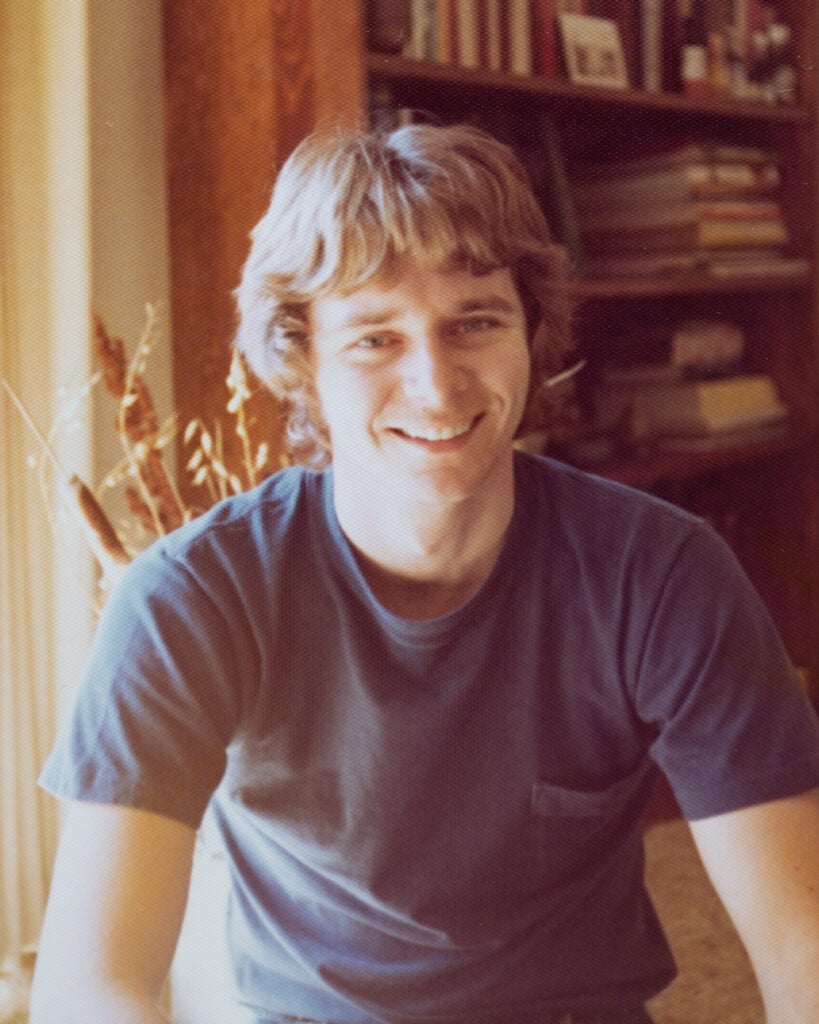

For more about the music used in this project, and to see some of my favorite photos of my father, scroll to the next section.

THE RECIPE: INDUSTRIAL MEATLOAF

This is an old school, hardy American meal from the industrial age. It’s something a hard working laborer would be happy to come home to, and my way of honoring the history of blue collar industrial labor my father played a part in.

The catharsis of this project was more about the writing than the recipe for me, so I will be forthcoming in admitting that I ripped off Martha Stewart’s meatloaf recipe, which is flavorful, moist, and excellent. I did at least make a few small changes: I use gluten-free bread, and I skip the veal. Instead, I just use a mix of pork and beef. I also skip the brown sugar in the glaze – it tastes just fine without it. Instead, I spike the glaze with a little cayenne pepper. I served mine up with some chunky mashed potatoes, roasted carrots, and frozen peas as an homage to the Swanson TV Dinners my father and I liked to share in the ‘80s.

INGREDIENTS

3 slices white bread (I use gluten-free)

2 garlic cloves, chopped

1 medium onion, chopped

1 celery stalk, chopped

1 medium carrot, chopped

1/2 cup flat-leaf parsley

18 oz grass fed ground beef (90 percent lean)

18 oz ground pork

1 large egg

3/4 cup ketchup

1 tablespoon dijon mustard

1 tablespoon Worcestershire sauce

1 tablespoon coarse sea salt (don’t swap for fine salt – it will taste too salty)

1 teaspoon fresh ground black pepper

A few light shakes of cayenne pepper

INSTRUCTIONS

Preheat your oven to 375 degrees fahrenheit.

Tear the bread into large pieces and pulse in a food processor until finely ground. You should have about 2 1/2 cups of breadcrumbs. You might need to pulse down another piece of bread if you don’t have this amount. Transfer the breadcrumbs to a medium bowl.

Pulse the garlic, onion, celery, carrot, and parsley in your food processor until finely chopped, and then add the mixture to your breadcrumbs.

Then add the beef, pork, egg, 1/4 cup ketchup (you’ll add the remaining ½ cup of ketchup to the glaze), the mustard, Worcestershire sauce, 1 tablespoon salt, and 1/2 teaspoon pepper to the bowl. Mix everything together using your hands. I like to take off all of my rings and wear plastic gloves while I do this.

Line a 5-by-9-inch loaf pan with long strips of parchment to make it easier to remove the loaf from the pan prior to serving. Set one strip down lengthwise, and set the other strip down horizontally, and letting them drape over the sides of the pan, so that you can use them like ”handles” when you remove the loaf.

Transfer the mixture to your loaf pan, gently patting down to fill the space.

Brush the mixture with 1/2 cup ketchup until smooth, and then sprinkle with a few light shakes of cayenne pepper.

Set the pan on a rimmed baking sheet, and bake until an instant-read thermometer inserted into the center reaches 160 degrees fahrenheit, about 1 hour 30 minutes. Be sure to let the loaf rest for 20 minutes after it comes out of the oven. This helps to keep the slices from falling apart when you cut into it. Carefully tip the pan to the side to pour off the grease prior to serving.

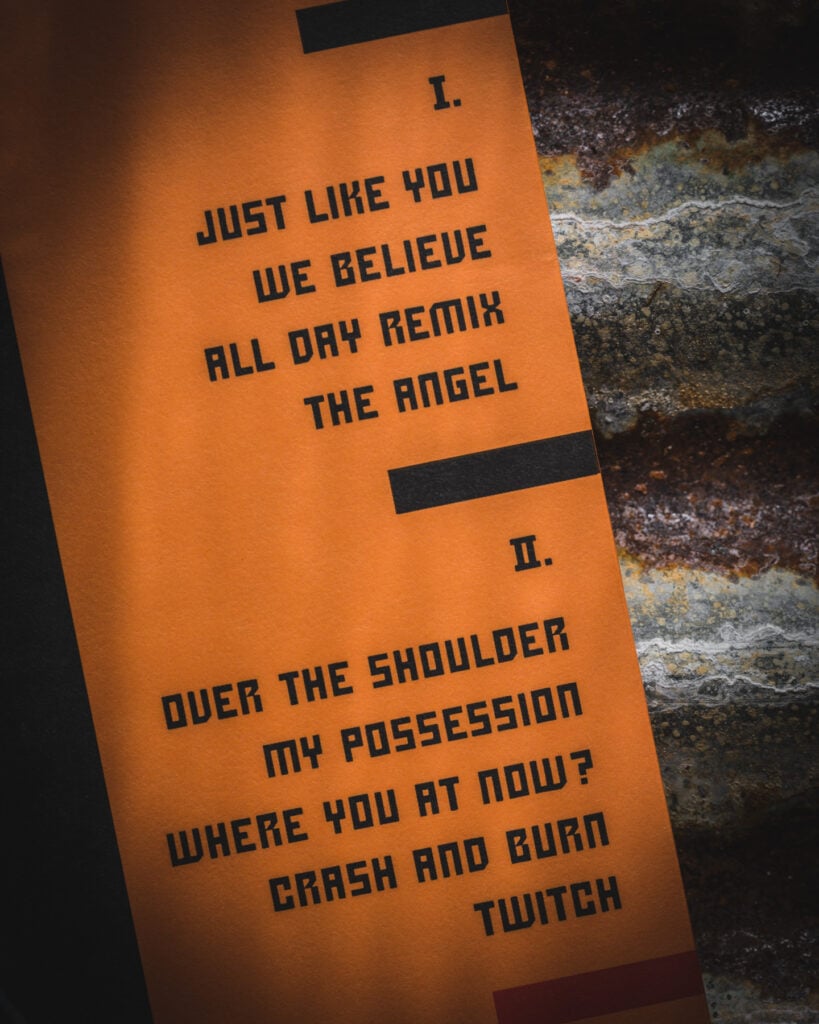

THE MUSIC: MINISTRY’S TWITCH AND PINK FLOYD’S THE DARK SIDE OF THE MOON

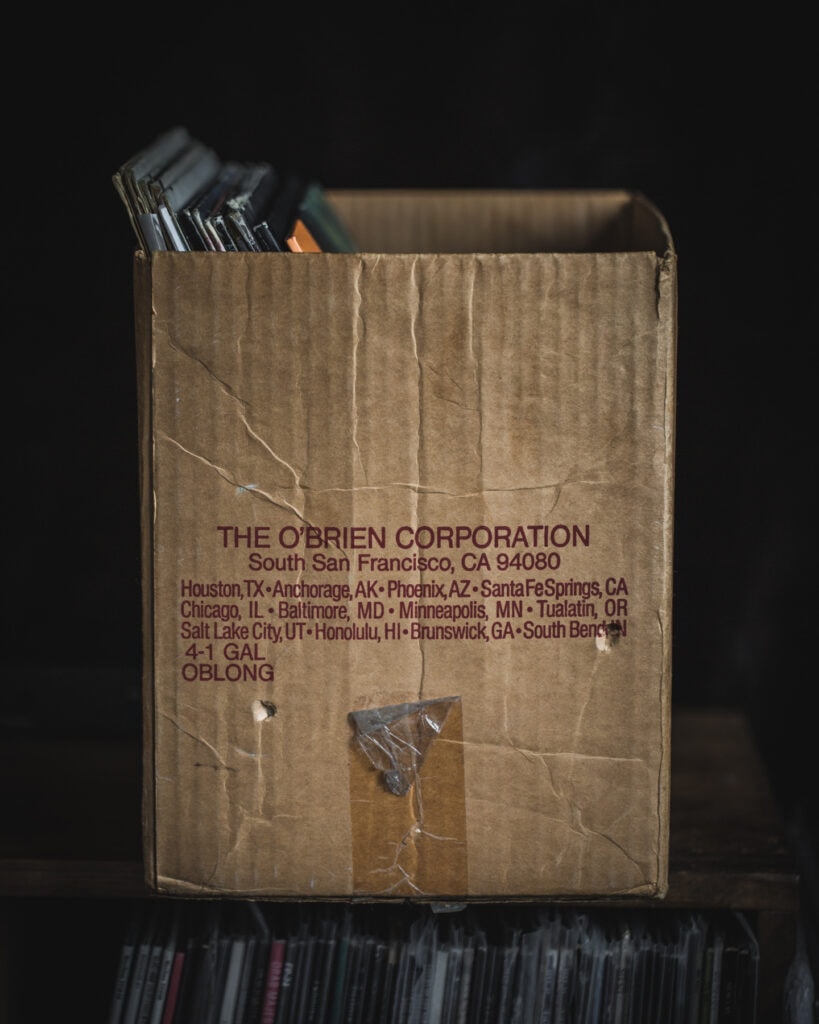

My father’s old records and the cardboard Fuller O’Brien crate he stored them in are some of my favorite possessions. His records mix with mine now, and for this project, I’ve worked with one of his albums, and one of mine: Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon, and Ministry’s Twitch, two albums that address the intersection of work, money, power, and violence. They are albums I came to connect deeply with after my midlife breakdown from overwork, which changed the way I understood what happened to my father, and his death. Listening to them became a way for me to infer what his experience had been, and a way we could have a conversation about what we had both been through.

I think music creates an eternal place that exists outside of time and space. Every time I listen to The Dark Side of the Moon, I resurrect my father, and we are together again. It seems magically appropriate that the album begins and ends with a heartbeat.

I don’t think my father ever heard Twitch, but I reckon he might have been down with it, connecting to its tricked out beats made from the sounds of the shop floor, and its lyrics about overwork, exploitation, and the abuse of power. His musical tastes were very hip, and he listened to a lot of new wave in addition to his aging hippie classics.

I knew I’d relate so much to this post. My father died the same age as yours, though I was 3 years older than you when it happened. My mother made our life hell – his, mine, my sister’s, her own. He didn’t work himself to death – he drank himself to death to escape the horrors of fighting a war he didn’t believe in and the family life he had to endure. He spent long hours away from that over-priced house my mother insisted she had to have, because being inside it was hell. It’s still hell to me, going there, and I have to prepared myself mentally for weeks before I can step inside. And I always stay as little time as I can. I knew I’d be flooded with repressed memories of my own reading this, but I have to thank you for forcing them out, for writing this, for being this open and courageous and brave and… candid. I admire you a lot, Courtney.

Oh Ruth, I’m so sorry. It is amazing the similarities between our experiences. My family’s giant house is no more, but I have many feelings similar to yours whenever I go to visit my mother at her new home. Thank you so much for reading.

I’m so glad you wrote this.

It must have been tough losing him so young

The piece brings warmth to the memories of my own Dad and helps with the grief of losing him.

Thank you.

Thank you so much for reading. I wish you peace, healing, and connection in processing your own grief.

Beautiful post, Courtney. The love for your father shines throughout.